- Home

- Schorer, Mark;

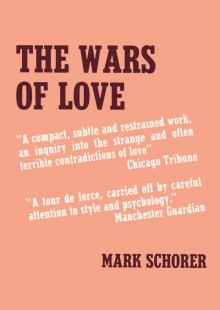

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love Read online

The Wars of Love

A Novel

Mark Schorer

New York

BOOKS BY MARK SCHORER

A HOUSE TOO OLD

THE HERMIT PLACE

THE STATE OF MIND

WILLIAM BLAKE: THE POLITICS OF VISION

THE WARS OF LOVE

For Eleanor and Kenneth Murdock

ONE

Summers in the Country, When Young

1

When we remember, at least, we are all artists. I try to remember 1924. And I know that whatever we are or profess to be in our active, present lives, magnificent or ordinary, even bestial, broken, and dull, we are by right of vanished lives, structures of memory underneath, and these are in some ways like works of art, although secret. Memory selects, distorts, organizes, and by these, evaluates; then, fixes! This is the artistic process, except for that final step beyond process which makes of the work an object capable of life and meaning outside ourselves, independent. But the operations of memory are our very selves, and are always taking independence from us. Thus our future is our past.

I begin in this unpromising way because what I have to write is founded on an exercise of memory, and memory can betray us as smilingly as a treacherous friend; I know, for I have told this story—have tried to tell this story before, and in the very telling it has somehow slipped away from me, so that it has never quite come out in the way that it should, and I am still determined that it can. And further, I begin in this way, reader, to give you that fair warning which is your right. I am, as you will see, an honest man; honesty, indeed, has been my profession: I have been paid to be honest. Being honest, I recognize at the outset that the deepest lies are those that we do not intend, those that we do not really know we have committed. Or think of it in a different way—like Joseph Conrad, when he wrote that “A meditation is always—in a white man, at least—more or less an interrogative exercise.” Certainly some of what I have to write here is meditation, and unless that were in part a matter of self-questioning, I should probably have no urgent desire to tell it.

Yet I am not a central character. I am less important in this story than any of the others. The others are, chiefly, three: Daniel Ford—you know the name; his wife, Milly—you know her face; and Freddie Grabhorn, their friend. The other woman, the incomparable Josephine Drew, who, as the chief witness for the State necessarily received a good deal of attention from the press and is therefore likewise known to the public, is not really a character in their story, although she is prominent in mine. I am only Grant Norman, once their friend. Of these, Dan, who was the weakest, was the best, and the center, surely, and it is surely Dan whom I wish to vindicate.

His difficulty was that common one, the difficulty of vocabulary. He had no other way of describing his act, and the way he took was wrong, simply wrong. When, almost at the beginning of his trial, in one of the few strong moments of his adult life, he said, and said so tritely, “Yes, I did it. I did it because they betrayed me; she—my wife, after all, and he—our friend”; when he said that before a crowded, gaping courtroom, he eliminated forever the possibility of establishing in its real terms the disastrous record. The defense attorneys, who had some idea of the true situation but not, I think, a very clear one, found themselves helpless in a net of clichés, and in the end they let the clichés stand; for the truth, the real nature of the betrayal, recited in a courtroom before that panting audience, would have given them less ground on which to rest Dan’s case. Like all human motives, which necessarily grow into abstractions, honor has meaning for most of us only in its baldest, dreariest terms, and those were the terms that Dan’s lawyers finally employed. Yet Dan’s was an intricate cuckoldry!

We think in patterns, in neat and recognizable and largely factitious forms of experience, and we impose these ready-made forms on events in order that events may be comprehensible to us; and this is the particular vice of the law, of judges, attorneys, and juries, and of their fellows, the habitual spectators, those anonymous persons who haunt and color criminal trials with the crude enthusiasm of religious fanatics. These are the black and white squares by means of which temporal justice can alone be made to seem, perhaps, an order; but they have little to do with human motives or with that absolute justice that some men are satisfied to think exists in another realm, and toward which anarchy, dissatisfied, aspires in this one.

Hence it was in no way surprising that the whole thing should have been recorded in the legal annals of this state as a commonplace sex crime, the simple triangle and one sick mind, and that Dan, a really harmless though profoundly dishonored man, should have been judged for his offense in the terms of this state, appropriate to his offense as it was understood. And yet his trial explained nothing, justified nothing. If this had been the conventional triangle, the catastrophe would have been very different: for that, Dan could not have found the strength to be so drastic. It may, therefore, be worth trying to straighten out the record, not, certainly, for any legal reasons—legally, Dan’s offense would have been the same, or worse because less explicable, and his motives of no importance except to that audience intent on verifying its assumption that man is both base and comprehensible—but for the human reasons. It may be possible to piece this story out so that it makes some sense on that more subtle and, psychologically, more violent level that alone can explain it.

For, to begin, these were subtle people—Milly, with her anfractuous pride, and Freddie, with his not quite simple jealousy—subtle in the way of the most profoundly immoral human beings, those who live alone in the involuted tower of willfulness; Dan, a weak man, subtle as a demonstration of the twisted forms that deterioration of the will can take. Of myself I need say nothing: the fact that, as this situation developed over the years, I had almost completely dropped out of the relationship, attests to my fundamental simplicity. But in the beginning we were all friends, and to understand—even for me to understand—what happened to our friendship and their love, it has been necessary to say as simply as possible these things.

2

At the head of one of those many lakes with Indian names in the Cherry Valley is a small town named Silverton. In winter it is buried in snow and isolated from the world; in summer it is hot, but its life enjoys an annual resurrection through the economic grace of the twenty-five or thirty families that come to occupy the large houses set on the sloping lawns above the lake. That, at any rate, was its situation in the first thirty years of this century, and I presume that today it is much the same. I have not been in Silverton for many years. In 1930 my father’s house on the lake was put on the block, together with other tangible remnants of the fiasco that was his life, and after that I had no reason to return. I was nineteen years old, I had moved far away, I had to use my summers to earn money, and I had by then drifted loose from the friendship that, for almost ten years, had been my summer life.

The beginnings of that friendship, how we first came together and came first to live so deeply in one another’s lives, elude me. They are lost in undifferentiated recollections of hot, insect-singing days and cooling nights, of thunderstorms over the lake and the tops of trees swaying heavily in the wind and meadow grass laid flat to the earth by rain, fragments of children’s parties—sticky hands and crepe paper and grass stains on starched white linen, of children’s lives when they are lost still in the giant lives of parents. Of those beginnings, nothing now coheres, but dissipates itself in memory like wisps of music or of smoke vanishing on wind. Being so near in age and our three houses standing side by side, Milly and Dan and I must always have been together, from our earliest years, yet nothing of the early years now shapes itself into event. Nothing coheres until that summer when Freddie entered, but from then on, i

n general outlines and in much of the detail, it is nearly all formed and clear to me.

Freddie was the outsider, a boy from the town, the son of a dentist who had many children, eight or nine. In a vague way, as summer people are of townspeople in a place like Silverton, we must have been aware of Freddie, but on a June day in 1924, he became, as it were, one of us. We were walking in a narrow, curving ravine between hills, along the dried-up gravel bed of a springtime stream. Birches grew up from us on both sides, their scarred white trunks thin and bright in the sunlight, leaves shuddering silver-green. There was a commotion of noisy birds above us somewhere, and we paused to look up through the patchwork of leaves, and then, as we stood together, three things happened in quick succession. Something whizzed through the air and up into the branches above us, there was a great fluttering in the branches and a crow plummeted to the gravel at our feet, flailing its wings, and Freddie Grabhorn came running around the curve in the hill ahead. He stopped suddenly when he saw us, stared and waited.

We stood with the dying bird between us, watching the final feeble efforts of its wings. The bird’s head was bloody where a stone had hit it, and the wings spread out slowly in the sun, on the clean gravel, like a fan of jet. We were silent. The wind stirred a feather. Beside me, Dan sighed deeply.

We looked up at the boy. He flicked a slingshot against the leg of his overalls with exaggerated idleness, and his eyelids flicked. Light leaf shadows wavered on his face like a mysterious mask and, perhaps, made that round and somewhat heavy face seem more sullen than it was. Then he smiled uneasily. Milly stepped round the bird and said to him, “Let’s see.” He handed her his slingshot, and she turned it over in her hands. “Show me how?” she asked.

He took it from her and when he had found a small round stone that pleased him, he placed it in the oval patch of leather that hung from the forked wood, pulled back on the rubber strips, and let the pebble fly up into the trees in an easy arc. Then he handed it back to Milly. Dan and I stepped round the bird and stood beside her.

“Aim it at something,” Freddie told her.

“The top of that tree,” she said, and aimed, and missed. She smiled at him, as if to apologize for her incompetence, and tried again. She missed again, and tried a third time. I said, “Let’s see it, Milly,” and she gave it to me. Dan and I studied it.

“Haven’t you ever seen a slingshot?” he asked us, and when Dan handed it back, he gave it once more to Milly. “You want it?”

“Oh!” she said with suppressed pleasure, but hesitated, her hands at her chest.

“Go ahead. I can make another.” He put it in her willing hands, and then he said to Dan and me, with a quizzical smile that seemed almost to say he was testing us, “Want to make some?”

“Sure!” we said together.

He dug in his pocket for a large knife with brown bone clasps. He opened its largest blade, sharpened to a blue gleam. “Come on then.”

We found a cluster of maple saplings that Freddie said were right, and we cut off three forked branches that he said would do, and while, under his instruction, we peeled the bark and notched the branch ends with the single knife, Milly practiced her aim. We sat in the sun on a grassy slope, and soon we began to hear her stones bouncing with light thuds off the tree trunks she was hitting.

“We need an inner tube, and some leather, like from an old, soft shoe, and some strong twine,” Freddie said.

Before we started back to my father’s house, where we could find these necessities, we stood around and watched Milly in the ravine. “Now I’m going to get a bird,” she said, and as she looked around in the treetops, her lifted face was thin and tight with determination. We waited quietly. Freddie put one hand cautiously on her shoulder and pointed to direct her eyes. She took aim, the stone whizzed, there was a noisy fuss in a tree, birds scattered in the sky, but no bird dropped. We waited again until a number had once more assembled in the branches. Then Freddie took the slingshot, fitted in his stone, aimed with one eye wickedly closed, and let fly. A threshing about in the leaves, and then a bird dropped heavily to a slope of hill and rolled over and down a little. I felt Dan jerk in a spasm of sympathy, and “Ah!” we all said, and again, but from a distance, we watched a glossy crow stretch its wings and fold into death; and going back, and always after that, there were four of us, not three.

The summer of 1924 became a summer of constant rain.

Freddie and I were thirteen, Dan and Milly twelve. I have observed since then the fickle shiftings and alterations of all friendship among children, how a group of children, small or large as it may be, is never long equal and unanimous. Three always push out one, and cruelly; four one, then two; then presently the whole alignment of loyalties changes again. This is the normal pattern, yet it was never ours, and ours was to be the consequent loss. Freddie merged his life in ours with a hungry passion, and if he had friends in the town or a life there, he hardly told us, and we, who had no curiosity about the village, did not, I suppose, ask. Our friendship and our life were what he wanted, and he wanted them from all of us, not from only one or two. He wanted, perhaps, not us at all, but what together we represented for him: the alien, the urban, and, through village eyes, the rich. He owned a bicycle which he had earned the summer before by delivering a city newspaper up and down the lake shore, and almost every morning, as the leisurely life of the lake houses was just beginning, Freddie would have finished with his papers and appear for the day. He had had a job as caddy at the golf club, too, but now he gave that up; he told us that it took too much time.

Milly had a special, feminine respect for his country wisdom and for his array of devices, of which the slingshot and the big knife were only the first two; and she welcomed him: if he felt some hunger to be one of us, she felt some reciprocal hunger to have him. Milly’s mother was dead. She had two brothers who were eight and ten years older than she, and a father, Gregory Moore. The brothers, triumphant young gods from Princeton who drove a Marmon and were perpetually in the center of those sporting and social activities which comprised adult summer life on the lake, were without interest in her, and that summer Gregory Moore almost never came to Silverton from the city, even for week ends. He was a man in his mid-forties then, with black hair turning white, and hot black eyes, and a remote speech and manner, so abstractedly gentle that gentleness was not at all the point; a romantic figure, if only because popular opinion held that for the seven years since his wife’s death he had lived in that death entirely, his grief and his sense of the gross injustice that had been done him, transformed into energies fiercely concentrated on his Albany law office. He opened his summer house for his children, and let the management of it rest solely with a housekeeper, Mrs. Colby, the capable, good-natured widow who likewise managed his household in the city. Mrs. Colby was professionally tolerant of us, and we had the run of the Moore house in a way that we did not have of our more conventionally organized houses. This laxity was no doubt arranged by Gregory Moore’s orders, issued perhaps from some vague feeling of penitence, since he gave Milly little besides his houses. Once Milly showed her friendship for Freddie, Mrs. Colby accepted him, too, with the same placid tolerance. In every real sense, of course, she was totally indifferent to all of us, and that did not matter—was, indeed, our advantage, except that most particularly she was indifferent to Milly. Or should I say that Milly alone needed something more than indifference from her?

And therefore Milly bound us, held us to her and held us to one another, and in Freddie, with his different motives, she found her perfect ally. I am wrong if I seem to suggest that either of them so early in life made any real calculations about friendship (although we later learned there was at least deliberateness in Freddie), but I am as sure that they both felt equally strong although different needs as I am that those early needs grew into their later, calculated, enmeshing deeds.

Milly dressed like a boy then, in dungarees or, more frequently, in shorts like ours, and a striped jersey. Sh

e insisted to Mrs. Colby that her straight blond hair be kept cut ruthlessly short, almost like a boy’s, with a fringe of it always falling across her eyes, but since this was not unlike the prevailing fashion among young women, it did not seem as remarkable as it was. She had serious, gray-blue eyes, and even though her white skin turned golden tan, her face had the lean look of the underfed with, sometimes, a strange translucence. She was a small child, small-boned, shorter than most girls of eleven and twelve, and thin besides; yet physically she was inexhaustible, the most able of us, the last to rest, and of a perfect grace. She held her head high even then, and she had a kind of presence, an authority that had nothing to do with her sex. She never argued or quarreled, even then, and when the rest of us began an argument, she had a way of taking charge and shifting the ground of discussion to gain a frozen peace between us.

Do I read this back into an unwarrantable past? I think not. Listen—That summer the rain became incessant, days and nights of it together, and trees and shrubs grew with a sickening vigor, crowding the shore and the houses, defeating gardeners, and gardens turned into fecund, unflowered jungles, sable green in the rain, and, when the sun broke through, steaming with damp, cloying smells of sodden earth and mould. We spent the rainy hours in the big attic of the Moore house, an enormous area under a multishaped roof, containing among other relics that provided distraction, a spinning wheel, a series of large plaster heads of German composers, a wood-burning set, a collection of naval flags, and, most remarkable, a suit of armor. At the center, the attic was high enough to support a hoop through which we could toss baskets, and for a week we amused ourselves with an abandoned volleyball net that we succeeded in stringing up from the uncovered beams. Yet as the rain continued, we grew irritated by our confinement, and after increasingly desultory play, we would settle down gloomily at the low windows just above the floor, as if they were squashed down by the ends of the steeply slanting beams, and stare out with desperate boredom on the drenched world below, the leaf-crowded, swaying trees, the naked, skeletal piers and diving floats, looking so impermanent from above, and the rain-glazed, empty gray expanse of lake that yielded us nothing.

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love