- Home

- Schorer, Mark;

The Wars of Love Page 2

The Wars of Love Read online

Page 2

Then one week end toward the end of the summer Gregory Moore appeared, and he brought Milly a present—a manual on the collection of butterflies and insects, a net, and a cyanide jar. This was a glass cylinder with a screw top, and it brought death without mangling. A half inch of gray powder covered its bottom, and over that was a layer of porous plaster which kept the powder in its place. We were told not to breathe over the jar when it was open, and after Milly’s father demonstrated the fascinating effectiveness of the jar with a fly he caught, further admonition was unnecessary. The fly died with a most durable and dizzying leisureliness, a lesson in finality. We spent a happy day with flies alone.

For a few days the sun held, but instead of swimming at last, we caught grasshoppers and June bugs and crickets and various butterflies. There were some large sheets of heavy paper in the Moore attic that we had planned to use for mounting, and it was over these that Freddie and I quarreled and began to fight. I do not remember how this came about, but I suppose, because of its size or condition or some merely imagined advantage, we both wanted the same sheet. Dan was there, but Milly had gone below for a moment, and Freddie had just pulled out the best sheet and given it to Dan, whom, I suppose, he favored. Then we both had hold of the next best sheet, and suddenly we were glaring at each other with resentment, and then anger, and in a minute the paper had been dropped and we were struggling. I can remember now the sensation of my curious, consuming rage, and I can remember feeling the fury of his. It was a battle, and what deep resentments it concealed or what it meant I am unable to say. We were on the floor of that attic, gripped together, rolling back and forth, and slashing out ineffectively until suddenly Freddie hit me maddeningly on the nose. Then, just as my nose began to bleed, I wrested myself free of his arms and, with a lurch, managed to straddle him and pin his arms down with my knees. Purposely I let the blood from my face spatter on his, while he helplessly wrenched his neck back and forth to escape it. His legs were kicking up and down behind me, but I had him firmly on the floor and he could not reach my back. I would have killed him then, if there had been any means, and wildly I thought of the jar, which stood on a table a little away from us, wondering how I could get it and, while he was helpless on his back, press it over his nose and mouth. It was a mad and murderous impulse that I could not attempt to execute since I had to hold him down. He was spitting and shouting with rage, and his face and hair were grotesque with my blood, which had fallen even into his eyes and mouth. Then he gave a great heave, and managed somehow to unseat me, and just as he began to pommel me again, there was another shout—Milly’s, a shriek of consternation and her own kind of fury. She seized a broom and with the flat end of it began to beat at both of us. “Help me!” she cried to Dan, who stood by paralyzed with fright, but Freddie and I had already separated, and suddenly our emotions were as limp as our bodies. We looked at each other without feeling anything at all but shame.

Yet what is gained by such an encounter is difficult to estimate: a kind of intimacy of the body, of flesh and breath, that binds as well as severs. I knew him for the first time, with the kind of knowledge one has later of a lover, where hate is intimate and deepest and impossible to abstract. And that was the chief source of our shame.

Milly said curtly, “Go down and wash,” and we went down together, and we helped each other, and at the last he looked at me with tears blurring his light brown eyes and said, roughly, “I’m sorry,” and I said, “So am I,” and the image of his face wavered in my vision. “Here’s a comb,” he said, and I took it, and handed him a towel.

We went back to the attic slowly and when we got there, Milly merely glanced at us. “We’re doing this together, not separately,” she said. “The sheets are for different kinds of things, not people. We’ll have committees. Grant,”—her eyes moved coldly and then kindly over my face—“you’re in charge of collecting. I’ll be in charge of killing. Freddie is in charge of mounting. Dan prints best, so he’s in charge of labeling.”

“Fair and square,” Dan said shakily, and how dark his eyes were in his still frightened face!

There were two weeks left before Labor Day, and on every one of these days we were together. The collection grew, and we even achieved a semblance of order and science on our mounting boards, but as the days dropped away, one after the other, Freddie sank into a gloom. With every hour summer was dying. I remember Labor Day. We were coming in from a row on the lake. Dan and I were at the oars, and when we reached the pier, we got out to make the boat fast. Milly and Freddie still sat in the back of the boat. He was staring gloomily at the floor while she explained to him with urgent sweetness that in winter the rest of us did not see each other either. Over the shimmering water, a flock of swallows dropped, and shot away, and we all thought the same thought. Another summer seemed impossibly distant, you could hardly believe that it could come at all.

3

It came, of course, the beautiful, hot, high summer of this state, the noblest season, a great green and golden Roman thing at full June opulence when we came again to Silverton. Gregory Moore came too, that summer, with his new wife, Miriam, and a sullen Milly, and his impervious blond sons, who were hardly younger than their new mother. At dusk the great elms around the Moore house attracted a hundred birds, and these at the end of each fair day broke into a desperate competition of song in praise of the day that was ending, a many-throated lyric high and sad and sharply lovely as are all things that help us feel at once life and death together in their true embrace. On our first day back, after supper, the four of us were sitting under the elms, with that torrent of song above us, listening to the notes rising and falling and searching through the air as if to find, if possible, just one new note beyond the liquid patterns to which those small throats were bound, when another voice broke over these. It came floating out through the open French doors of the house, over the terrace, over the lawns, under the trees—the voice of Miriam Moore, singing, I suppose, some lied, to an uninsistent piano, and singing like the birds, as if the heart must break with the double stress of joy and sorrow. The voice soared and clung and soared again, rich coloratura, a very presence in the lavender air, an urgent pleading that, in our surprise, pulled us forward toward it where we sat, and then had us up and on our feet. We walked to the terrace and stood at the open doors, looking in at the cavern of the shadowed room. It was lit, in so far as it was lit, by banks of candles that stood in tall holders on either side of the black mass of the piano, each flame long and still and candent in the breathless room. The woman we could not clearly see—only the vagueness of a pale, soft dress, the gleam of shoulders and of pearls perhaps, the dark head; but near the doors sat Gregory Moore, in profile, and we could see his face clearly against the dark of the room as the fading sunlight fell upon it. We had no words for the feeling in that face, for the feeling that pulsated in that room and filled it, but it was more present to us than language could have been. We had come upon the very heart of privacy; we all felt it; simultaneously we dropped back, as if we had been ordered. No one had a right to look upon that face or upon a face like that, scowling without anger, at once naked, ravaged, hungry, gray with adoring. It was the first time that I had seen—these are the little words we later find—the face of a man in thrall.

We dropped back silently and stepped down to the clipped grass, and when we turned to stare at one another in surprise, we saw that there were three of us only, and when we turned to the trees, we saw that Milly was there, had been there all along, looking away from us, leaning against the trunk of a tree, small beside it, as if she were somehow diminished by the trees, or the dusk, or the weight of sound. But now the birds’ song was dying, thinning out and settling into fitful chirps, and the woman’s voice stopped. We looked back to the black entrances into the room, from which silence now seemed to pour out into the dusk, and then we went back to Milly.

We had no plan, but she said, “Let’s go,” as if we had, and she said it in the small, despairing voice

of one who does not know the luxury of alternative.

We walked home with Dan.

When we remember, we are all at least bad artists, and I may carry with me—the singing birds in the trees, that dark room and the summer twilight, the candles, the music, the singing voice, the stricken, captive face—I may have drawn here (and drawn up from what obscure passages of time and mind?) a very faulty image of love. Yet it is the image that I carry, and it lingers, and in later years I hear her not simply singing, but singing a particular song that, I suppose, I have given her, Wolf’s “Und willst du deinen Liebsten sterben sehen,” and the thraldom of Gregory Moore, which was in reality a complete gift of his being, has sometimes seemed to me an infinitely desirable state. For I was in time to lose, I do not know how, the ability to be careless of myself.

Bianca and Daniel Ford, Dan’s parents, are a different kind of remembrance. That summer, and from then on, with Miriam there, transforming the once casual household into an ordered elegance and creating in her marriage that atmosphere of hot, enchanted privacy, we were not to play much around the Moore house, but seem to have chosen the Fords’ instead. And the Fords were like a king and a queen, remarkable in confidence and in the assurance of a superior equality and the sense of their own inevitable rightness; or like, at least, a toy king and a puppet queen, for they were not, I think, without their comic aspect. They were too small as physical beings to assume such enormous complacency as was theirs, so that one had the impression that they could not fill their moral clothing. There were certain affectations—Daniel Ford’s dark, solid-colored silk shirts made for him with sleeves a little full and cuffs a little tight, so that they gave the impression of just not being blouses; a beret when he walked; a black beard, pointed and precisely trimmed; and yet with these, denying any mere bohemianism, expensive business suits tailored with utmost punctilio, or beautifully conservative linen or Palm Beach or light tweed jackets and knickerbockers. Bianca Ford might have been his deeply sympathetic sister. She accentuated the heavy, lily whiteness of her skin by using very dark red lip rouge and a good deal of dark make-up for her eyes. Her hair was black, pulled tightly away from her face into an extravagant chignon that positively hung on her back, and from her exposed ears swung lavish pendant affairs that glowed and flashed. Her clothes, even her daytime clothes, managed to suggest not dresses but robes, and her shoes were always colored—green and purple, garnet, maize, and blue—royal shades. They were absurdly small people, not more than five feet four or five inches, and of exactly equal height, and yet, while they were no doubt regarded as the eccentrics of the summer colony, theirs was apparently an amiable eccentricity, and no one laughed at them.

Accepted by others as of at least equal stature, they treated themselves like royalty. At table, they always sat side by side. If they were dining alone with Dan, they were together at one side of the table, Dan opposite them. If they were entertaining, they were together at one end of the table, the guests dispersed down the sides. One thought of them as always together, as if, whenever they appeared, they were making a public appearance or even a pause in a progress, and one wondered a little what remnant of regal ceremony they clung to in their most private interchanges, for I think that they were incapable of abandoning it entirely, lest they should have lost the illusion of divine right by which they lived.

This I do not of course know, but I believe that they were a man and woman without passion, a man and woman perfectly matched and perhaps almost entirely unmated. They created an exotic atmosphere that was yet dry, devoid of romance, and in this, they were the very opposite of the Moores. Dan was their only child, yet he seemed not so much their child as their equal, who shared their calm and their equanimity. They preferred each other’s company to the company of others, and, without ever exactly shutting themselves off, they lived a little aloof from the rest of the summer colony and always gave their friends a just adequate awareness of their difference. Bianca Ford helped her husband in the management of The Ford Gallery, and thus, unlike other wives and mothers, she not infrequently spent at least part of her week in town with her husband. For brokers and bankers and lawyers and manufacturers, as for their wives, the ownership of an art gallery must in itself have justified a certain eccentricity of dress and conduct and point of view, as Bianca’s part in the management of the gallery must have justified her sporadic presence at Silverton and her disinclination to spend her afternoons at the bridge table, or, in 1925, in concentration over a ouija board. The Fords had no questions to ask; they merely averred. We read, we lounge, we sit together in the sun on a wrought-iron settee, our hands just touching, impassive; we never quarrel, we are in perfect poise, we are right.

Dan could not judge them, naturally. He was bred without the tools for judgment. Freddie, it developed, loathed his home; Milly yearned for hers, but was denied it; I—well, of that later. But out of one kind of passion or another, out of the kind of grating and disharmony that all passion must entail, each of us fashioned judgment, and a will that would shape action, and in this Dan differed. Yet, being the child, he did not so much aver as accept. His parents had given him nothing to reject, nothing either to yearn for or to deny in them. They gave him the gift of their own kind of confidence; since it was a gift, since he received it only and had not been asked to form it, it was in him necessarily bland, without insistence or force. In friendship he was passive, and therefore to him each of the three of us was most deeply and intimately drawn. We felt perhaps an equal friendship, but for Dan we also felt protection.

He was a slight, brown boy, with bright black eyes, and thick black hair, straight and short like beaver fur. It fit him like a cap, rounded low over his forehead, curving in at his temples, and gave him an appearance of exotic distinction. He had a small brown mole, just darker than his skin, beside his nose, and his color under the brown was dark red, as if borrowed from his mother’s lips and diffused along the line of his cheekbones. He was a year younger than Freddie and I, with a lighter and somewhat breathless voice, and even then, when we were all simple, he was more naïve than we and in a way, therefore, more sensitive to the condition of others.

We walked along the lake shore through the thickening gloom. Milly walked shufflingly, with her head down, striking angrily at bushes and the ground with a stick she carried, and no one said anything. Freddie tried to whistle, but the bright notes died tunelessly on his lips. I picked up a white stone and tossed it in the indigo water. Constraint was heavy, like the silence between us. Then suddenly Dan skipped a step and said cheerfully, “My mother plays the harpsichord.”

Milly sniffed impatiently.

“In the city, I study the ’cello,” he persisted.

“Who doesn’t know that?” and whissh! she brought her stick down through the air.

Dan hesitated, and then blurted bravely, “I’m studying a Haydn bourrée.”

No one took him up. Now we had come to the Fords’, and we stood on the grass beside an iron deer that glittered darkly in the lights that fell aslant from the house through the trees. Milly wove her arms in the cold, rounded horns, and wound her fingers among the well-rubbed tines, so that she looked as though she hung there helplessly and would be tossed and gored by the iron thing. On the darkened lake a launch coughed and sputtered and gave a distant roar, then raced off into a diminishing hum. Far off somewhere a man’s voice rang out over the water, and from a pier nearby laughter lightly died. Along the shore, yellow light lay uneasily on the water in reflected swathes, and the evening bats swept and circled over them in their restless hunt for insects. In the distance a phonograph played a spasmodic song, and from the broad porch of the Ford house a Negro voice called softly, “Master Dan, it’s time.”

Milly’s arms slipped down and she put her head on the cold arched neck of the deer and began to cry. Her thin shoulders shook on the inflexible shoulders of the deer, and the muffled sound of her sobs said that she must have been biting into the flesh of her arm to subdue them. No

one had ever seen her like this, and none of us knew what to do. We inched toward her stiffly, and hesitated. “God damn it, God damn it!” she began to say through her broken sobs. Then she straightened up and impatiently wiped her arm across her eyes.

Freddie spoke first. “Gosh,” he said, “when I was a kid, I used to run away from home, just go poking around town, and you know what my mother did? She got some rope and she tied me up to a post in the back yard, with about ten feet around the post to play in, like a dog on a leash, one whole summer.… Talk about tough!”

It was the first time that Freddie had told us about his home. Dan stared at him and Milly looked at him obliquely, doubtfully. His revelation made me bold. “My mother drinks,” I said.

Milly sniffed again. “Everybody drinks.”

“Too much, I mean,” I said.

“Master Dan! Master Dan!” The soft dark voice came through the darkness like a kiss.

“Coming.”

We walked up the lawn to the porch with him. “Tomorrow …” Milly started.

Then two voices said “Hello” together, and we looked up. On one of the wrought-iron balconies which hung suspended from the upper windows of the house stood the Fords. They were framed in an opening filled with golden light and bounded by the scallop shape of heavy drapery. We could not see their faces, only their black silhouettes cut sharply out of the yellow light as they stood there together, two benign presences, like some coupled statue not quite life size from antiquity. “Hello,” they said again, together, as if they had rehearsed.

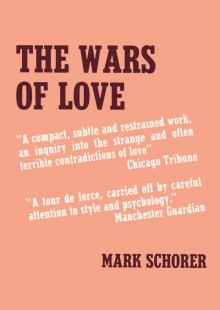

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love