- Home

- Schorer, Mark;

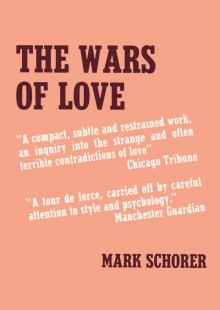

The Wars of Love Page 8

The Wars of Love Read online

Page 8

I asked her, for example, about Gregory and Miriam Moore, and for the few moments that she answered, Freddie even left the room. “They’re still there,” she said, “in Albany. Engrossed. It really was truest love. How I hated it!” And her brothers? One, it seemed, was in her father’s office, the other in a Wall Street brokerage firm. She seldom saw them. Then it seemed positively crude not to murmur something, if only the most cursory expression of sympathy, to Dan, about his tragedy, and so I tried. Milly took his hand in a spontaneous gesture of communion and protection and he asked wanly, “You knew?”

And then Freddie, who had come quietly back into the room, said briskly, “But tell us, Grant, what are you doing here?”

The question startled me. For a moment, with my sense of being a stranger, I thought that he must mean there in that room, with them, and I said, “Here? Why—”

“Here in New York.”

“Oh, yes. But haven’t I told you that?”

“No, you haven’t. Not a word.”

Milly said, “Another cocktail, Freddie dear, please,” and Freddie busied himself again with his bottles, his ice, his pitcher. Now I saw that Dan had fallen into a funk of grief, a reverie remote from us, his eyes glazed over as he remembered them, and I said, “It’s not very interesting work. Not half as interesting as yours must be.”

“But, Grant, interesting or not, we want to know,” Milly said, and glanced sidewise, apprehensively, at Dan.

Freddie, starting up with his pitcher, said, “Of course, we do.” He began to fill Milly’s glass, which was nearly full.

“Not for me, Freddie,” she said. “For Dan, for Grant, and you.”

He filled Dan’s glass and Milly took it and put it in Dan’s hand. He sipped at it, and that film lifted from his eyes.

“Not for me, thanks,” I said, and Freddie filled his glass again, and they were all looking at me.

“Well, you don’t read The New World, I gather.”

“No, why?” Milly asked.

“I’m on the staff there.”

“Oh. Well, that’s interesting, isn’t it?”

“For me, yes. But I’d guess it’s pretty far away from what interests you.”

Dan had said very little. Now he spoke. “That’s the magazine for which Drucquer does the art.”

“No,” I said. “He’s on World Progress. They’re much alike, I suppose.” They were not alike, of course, except in their appearance, and it seemed astonishing that Dan should be so distant from both that he would not know which critic of painting was associated with each. But he seemed hardly to notice my correction.

“Drucquer,” he was saying with a quaver. “An ignorant man.”

“Is he? I wouldn’t know. I’m not up on painting. I read him occasionally, that’s all.”

“Drucquer.”

“Drucquer,” Freddie broke in. “He’s typical. There’s only about one civilized art critic in this town. Just about one who writes out of real knowledge and feeling and a wide view of art as a whole. But the place is full of the Drucquers! The little dogmatic impressionists. Sometimes I think that I could do better.”

“Why don’t you try, Freddie?” I asked.

“I’ve been tempted.”

“Drucquer,” Dan said again, doggedly, as if speaking out of a stupor. “Drucquer.”

And Milly cried, half in agitation, half in gaiety, it was hard to know which, “Oh, darling, Dan, dear, forget him, he doesn’t matter!”

I watched Milly. It was fascinating to watch her. She was holding both his hands, those beautiful hands that had already made me think that he ought to make things, not to sell them. She held them, stubby brown hands with short fingers and broad, impeccable nails, in her white hands, plied them and pressed them, and urged him, with such sisterly solicitation, to please forget all that, that again I had the notion that here there was an excess, I did not quite know of what, but surely an excess. Now she was all the first Milly, the calm, possessed Milly who used endearments without thinking of them as endearments, the dear, darling, how-lovely Milly, all easy, all understanding, all—as I then began to see—all loving, and all untouched.

“Drucquer,” Dan said again. “I can’t be asked to meet that kind of opinion. The thing is, Grant, you see—”

It was now that I knew that there had been a change in him. I did not know how deep that change was, and certainly I did not know the sources of it (I was unwilling to believe entirely in their explanations), but there had been a change, that I did know. He spoke with an odd querulousness, in an almost petulant voice like that of a spoiled child—he who had never been spoiled, only always beatified. I groaned for him.

“You see, we have this new Van Gogh. An early work, apparently. We acquired it very recently, and last month we showed it.” He hesitated. “Or do you know?” he asked suddenly.

“No, I don’t know. I haven’t followed art news. Now I will. Go on, Dan.”

He gave me a stricken look. Milly’s hands rubbed his. Her eyes widened and narrowed at me. She said, “This is so silly. Freddie, for heaven’s sake, a drink.”

Freddie had rather sunk down in his tapestried chair. He roused himself and looked owlishly at all our glasses. Dan’s was empty, and Freddie’s own was empty, and once more he poured the ice water from his pitcher, dropped in new ice, measured with precision, slowly stirred, and moved among us. As he poured another cocktail for Dan and another for himself, Dan’s voice started up again.

“This Drucquer. He published a thing on the show a few weeks back. You didn’t see it?”

“No,” I said.

“And I wrote him. And today he came in. And he wanted to argue.”

I had been watching Milly, who looked depressed and beautiful, and for the moment that Dan spoke, I had closed my eyes, so that I only heard him, did not see him. The voice was like that of a superannuated invalid discoursing on his ailments. I opened my eyes again and saw that he had got his hands out of Milly’s, and they were fluttering before him in a foolish, ineffective way. I was about to leap up and say something directly to him, something that would bring him back to me, and to himself, when Milly took up the new cocktail and tried to put it in his hand.

“Darling, it’s so unimportant,” she implored him.

“Oh, I suppose so,” he agreed, and let his hands fall on his legs, but I did not feel that he was relaxing so much as letting something fall inside himself as his hands fell outside, letting something go.

Impressions had come too fast that evening, and they were all undefined, but through them all was the dominant impression of uneasiness, of Freddie watching, of Milly shifting back and forth from candor to some concealed complicity, of Dan, in spite of his appearance and first easy friendliness, living in some dark distress or deep indifference. But see how confused and vague even this impression was—distress or indifference? It could hardly have been both, or so I thought. And Freddie had ceased to watch at just the moment that Dan was most distressed, had fallen, then, into a kind of drunken indifference of his own.

The drinking, and Milly’s encouragement of it, had impressed me, too, and as we moved now into another darkly paneled, heavily beamed room to dine, I could not fail to observe that Milly and I were nearly sober, and that Freddie and Dan, if not quite drunk, were certainly not sober. There was wine at dinner, and the effect on the two was different. Conversation turned almost at once to childhood and Silverton, and the wine, together with Milly’s animated recollections, brought out in Dan something of his old animation, a dance of laughter in his eyes, the light breathiness into his voice. Freddie seemed content simply to be there, and sat in heavy silence as he emptied glass after glass of wine.

We were sitting at the middle of a long table. At the empty ends were thickly clustered candles and large blue hydrangea plants in silver bowls. Freddie and I sat side by side, and opposite us, side by side, sat Milly and Dan. It was that old pattern of the senior Fords, and as I looked across the table, I had a stro

ng conviction that here again I beheld the relationship of Dan’s parents, or part of it—the brother-sister fondness and equality, the imperviousness to passion. What was missing was the eccentricity, the vast security, the comic superiority. And a child across from them to share in it all. Instead, they had me, they had Freddie. And yet, as I laughed and chatted with them over events that were stone dead to me, their pleasure in recollection warmed me. Quite simply, I loved them.

Freddie may have been listening or he may not have been. I glanced at him occasionally and saw him perfectly solemn, perfectly happy, and once he turned to me and his light eyes were filled with perfect benignity. “Come often,” he managed. Could I have been as mistaken in him as that muttered invitation made me feel?

After dinner, over brandy, Dan suggested music, and we listened to a lot of recordings of Scarlatti. The thin, rigid patterns of sound could not fill that room, which required more than the little sonatas of Scarlatti—the late Beethoven, at least—but something in the very smallness of the music was soothing to all of us, or so I felt, and as those fugal airs ran up and down, with their precise grace and absolutely controlled charm, I felt myself sink into a deeper happiness than I had known for a long time. Dan and Freddie drank a good deal of that brandy. I did not and Milly did not. I did not need to. What I felt inside me was warmer than any benefit of liquor could have been. And then, through all of that florilegium, Le Donne di Buon Umore, I sat looking at Milly’s profile. The proud head was lifted alertly above that foil of high black collar as she listened, and the music seemed like an adornment to her, and as I let myself reflect in happy idleness on their likeness, the kind of beauty in the music and the kind of beauty in her face—the composure that suggested not struggle but interplay between its own small elements which did not include passion, passion that makes struggle and makes large elements and makes composure great—and from that, on those two Millies, this calm, friendly one who listened to Scarlatti now with the three of us, and that other, almost cold one who, over her cocktail, had remembered my cousin Margaret whom I had nearly forgotten—with this, my mind at last organized at least something from all that welter of unsettled impression which had been this evening.

It struck me that Milly belonged to both these men and yet belonged to neither. Or perhaps I should say that she had taken to herself qualities of each of these men, possessed herself of them by a kind of moral osmosis. The first Milly, who was without guile, was Dan’s Milly; the other one, who was tensely cold, was Freddie’s; and neither was a woman. The first was a more gracious version of a part of the child that she had been. The second was a frightened creature who had fled outside the limits of her sex and was thereby also another version of another part of the child that she had been. And thus I faced an irresistible conclusion: there was still a third Milly, Milly herself, a potential woman, more tender, more beautiful, who needed only to be found to be awakened; and she was mine.

The discovery was thrilling, like new knowledge, when, in a moment, we are taking a felt step beyond what we have been, and I was suddenly alive with that knowledge, vibrant as taut wires in a wind. Some wilder music than Scarlatti’s sang up and down in my blood, some sharper, more stinging wine of happiness than that flood of youthful love that overtook me at dinner. And for the moment I was completely outside speculation, either as to the practical steps by which the goal of this knowledge was to be attained, or as to the difficulties, moral difficulties among them, that the pursuit would entail. I existed completely in the awareness alone, in that galvanized state of new perceptivity, and then, without meditation, I knew that for the first time since some lost point in my youth, everything had come into focus again. I thought that I knew why I lived.

I have felt it necessary to define the force of this emotion because this emotion was to bring me again, for a short time, into an active role in this strange relationship, and the justification of my actions must lie in part in the rightness, the inevitability of my feeling on this first night as we listened to antique music which, by its very incongruity, had plunged me into this experience of the immediate, of myself as collected, like an athlete ready to spring forward at a starting line, on the very pitch and point of the present. The rest of the evening was, of course, an anticlimax. During the remainder of the music I found myself in several unguarded moments staring at Milly’s face with eyes which, had they been observed, would surely have been described as greedy, for I felt my greed. But when the music was over and conversation between the four of us picked up again, I was ready to leave. It was late. We were once more on the subject of my work. I had no interest in discussing it, I wanted to save that, and the whole world of value that it carried, for Milly. Let her take that from me, when we found our time, as she had taken these other qualities from them in time past.

But still, out of their rarefied world, they questioned me—Dan ingenuously, Milly quite seriously, Freddie with his air of sly knowledge beyond ours. I said what could be said, so late on a liquor-soaked evening, about the function of liberal journalism, until at last Freddie made the expected remark about starry-eyed unrealities. I almost loved him for it. It was so right that he should have said it. It brought the discussion to an end, and it gave me a point at which to begin.

I asked him where he lived, and when he told me, I suggested that we walk together down a stretch of Madison Avenue to clear our heads. He seemed glad to. When we left, Milly laid her hands on my arm for a moment in a way that made me tremble, and I did not very much want to look at Dan.

I have had my uncertainties. I have had moments, yes, hours, when I have heard myself saying, I want assurance, I want someone to tell me that I am doing the thing that is right. Down twenty wintry blocks Freddie walked with me, and I had no such uncertainties then, no, not then, nor over that nightcap at last in an empty bar when, as before, I plied him with questions, trying to trap him. I could not know what it was that I wanted him to say, but I knew that there was something he could say. He seemed a villain. And, Say, say, say, every question of mine beguiled him, but he would say nothing, he was all clever, befuddled friendliness.

“Come often,” he had said to me at dinner—but who was he, to say that?

2

Not greed; no, after that first discovery of what could yet be, not greediness. Call it hunger. Hunger has a strange capacity of emulating the thing that it is not: when you feel hunger, the sensation is of something that is eating you, gnawing at the empty bowels, at the stomach groaning as it shrinks. Something like this is what that desire became, so painfully engrossing that I was able to tell myself that I had never loved before. But to feed that hunger was another matter from feeling it. The feeling of it had come like an assault, a sudden blow, had struck me down in empty aches, a visceral agony of longings. The feeding required, quite simply, a plan, a strategy, and that I did not yet have. But I thought that I knew now why I lived.

I went constantly to that great, dark apartment on upper Fifth Avenue. I went at the hours that I could manage, but what I could not manage was to be alone with Milly. Before dinner, at dinner, after dinner, it was always the same: Dan was there, and usually Freddie, too. Twice I telephoned and asked her to meet me for lunch, and each time she brought both of them along: she had just stopped by at the gallery on her way to meet me. Two or three times I tried to arrange that we have a drink together after I could leave my office: once she brought Freddie, and the other times she could not, she said, manage a meeting.

She was all charm and loveliness. Always there were those embraces, the sweet smelling arms in my arms, on my shoulders, the glad and, to me, meaningless kiss of welcome, and, when I tried to make it different, the just perceptible stiffening in her body that yet was not allowed to disrupt her willed ease. But clearly she knew now why I came! Through the foolish blur of sentimental benignity into which the four of us would sink, I would sit silently and let my eyes settle heavily on her face, while her eyes sought a flurried escape, and Freddie’s burned suspi

ciously on me, and Dan’s, impervious to all this interchange, turned inward upon his scorched self. I could not press hard: I knew that to have her at all, I had to accept the group benignity. If I disrupted that now, then all was lost. And so, under the surface, this was our skirmish: she to keep me without having me; I to keep the circle intact until I could have her.

Under that surface flowed other currents that were deep and strange and that I could not chart, and did not much want to. But it was impossible not to feel at all times the difference in the two men, and the split in Milly that their difference seemed to compel. For Dan, Freddie felt and exercised a nervous and aggressive protection, but of this, as almost of Freddie himself, Dan was unaware, or seemed to be. Freddie was simply a fact, he was simply there, useful, perhaps indispensable, but in no need, apparently, of Dan’s particular regard. Milly’s he had, and in Milly’s life and nerves his nerves played a part; they altered her, changed her constantly from Dan’s warm, sisterly companion to Freddie’s own alert, rather cold, sharp, spasmodic, suspicious—well, what?

That is what I could not fathom: what? And yet, this split that always ran through her and through her conduct on every occasion, made me suffer, made me burn with impatience, and burn with desire for the woman who was not yet there at all and whom I could create and save from both the sentimentality and the threat of fury in the two false women that she was. And in doing so, I might, besides, save myself from my own odd kind of loneliness and misery. For I had these. But how? How?

I went there one afternoon early in March at three o’clock, left my desk two hours early, and found her alone at last. She was startled, and covered her alarm with chatter. There was no embrace that day, no quick kiss; but a swift retreat into a flutter of “Darling, how nice, come in, I’ll get … I have.… Tea, darling? But it’s so early … I’ll ring.”

I followed her across the room and caught her arm. “No, don’t, Milly. I don’t want tea.” And I laughed with a silly feeling of triumph. “It is early, isn’t it?”

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love