- Home

- Schorer, Mark;

The Wars of Love Page 6

The Wars of Love Read online

Page 6

6

Margaret Linden stayed with us for a month, and her visit made another difference. The year between our ages did not seem to matter, but the two years between Margaret and Milly might almost as well have been twenty. Milly wanted to be younger and less of a woman than she was; Margaret wanted to be older and more of a woman, and worldly, besides. She smoked cigarettes in a long black holder and she played bridge with the kind of easy concentration that makes champions. Milly hated bridge and loved tennis, but Margaret had not even brought a racket. There was also the matter of the fifth person, a difficult problem at either tennis or bridge, and when, for example, I suggested that we all sail, Milly would point out that the boat was really too small and that she would stay at home. After a few days, I gave up trying to bring them together, and I necessarily spent my time with Margaret, and with one or two slightly older people whom my mother would invite around. Then, after Margaret left again, I tried to renew the relationship with Milly that we had just begun on the day of Margaret’s arrival, but she pushed me away, this time very firmly. She said, briskly, “Let’s forget that messy business and be what we are, friends.”

I said, “All right, if that’s what you want.” I could say this honestly, for that excitement had given way to a new one, and when Milly said then, “Your cousin had a good time, didn’t she?” I answered, “Yes. She’s coming again next year.”

She came almost as soon as the house had been opened, and stayed again for a month, and so again, Milly and Dan and Freddie managed without me. Again, I made a few efforts to bring Margaret into that circle, but even though Milly was older now and looked it, and could very well have met Margaret on her own ground, she was cold to her. It was the awkwardness of trying to bring Margaret into our friendship that showed me, for the first time, that our friendship had grown into a strange one.

That was the summer when everyone sang “Chloe” and “Blue Skies” and “Ain’t She Sweet,” and these songs beat out the tempo for the hot, troubled, purely physical thing that sprang up between my cousin and me, and exhausted itself, all in that month. Perhaps it was because I had no illusions as to who it was that played the stalker’s role in this affair that it left me, after Margaret had gone again, so at odds with everything, myself included, as if this relationship that I had wanted and taken, had somehow, in fact, taken me. And I was left with an ill-tempered sense of being incapable of repossessing myself.

My relationship with the other three was never the same again. I was suffering from some Ich-schmertz that was still outside their experience, and even though this was the summer that we found we were no longer hunting for fishing bait on Saturday nights, clambering around on our hands and knees in the dirt of damp places with a flashlight, but were going to dances at the club instead, and that on Sunday mornings, instead of meeting at sunrise to begin our day on the lake or in the woods, were sleeping until noon and then meeting on the golf course, even though, that is to say, this was the summer that marked our movement over into adult pleasures, I was no longer of them, as I had so long been. The original, naïve intimacy of the other three had not changed, and that, plus my own un-ease, expelled me.

Milly was beautiful. The ragged blond hair of earlier years was now always groomed, and for the first time the charming contours of her face were allowed to stand wholly clear. Her forehead was low, her cheeks, under the high bones, rather hollowed out, her chin, fine and pointed and perhaps a little cruel, and her neck, round and slender and long. Summer made her brown, with a high, warm color in her cheeks, and her gray-blue eyes were vivid and startling in their contrast with that skin. Her mouth in repose was perhaps a little petulant, almost sullen, and yet it had the expression not so much of the spoiled child as of the badgered one. So, too, was her manner with almost all people except the three of us—abrupt, more than that, almost self-protectively rude, as it had been with Margaret Linden. Whatever it was that beset her mouth showed itself more clearly in her relationship with us, and I knew now that we were no longer so much her friends as we were the indispensable props to something that appeared to be vanity and may have been, but was also, certainly, something much more.

Freddie and Dan went on in what was apparently the old way, making up with a doubled devotion, perhaps, for my lapse. I dropped more and more away from them, and after a while, as that summer drew on, seeing them together, seeing that intimacy still hold that should long before have altered its character or been abandoned entirely, and trying myself occasionally with awkward unsuccess to renew it, I could not be very sorry.

That year I finished school, and because our relationship had trailed off into the false thing that it had become for me, it was as well that I did not have a chance to go to Silverton the next summer. My mother had offered me her companionship in a trip abroad as a graduation gift. My father went to the country alone for the latter part of that summer, and when my mother and I came back from Europe after Labor Day, we went up to Silverton for a week end in order to close the house after his use of it.

Late in the first afternoon I walked over to the Fords’ house and found that it was already closed for the winter. That iron deer stood in cool shadows, head lifted as if to sniff the rain that was coming, and I walked on over to the Moores’ house. That, too, was already locked up, the shutters nailed tight, the doors boarded over. I stood on the terrace that lay above the lake and watched the sky darken. Far away in the valley hills, thunder rumbled and gurgled, and the wind that came ahead of the rain ruffled the dark water as though it had a surface of indigo feathers. The empty lake and the blackening landscape made me yearn, suddenly, to see them again, and the desultory chirpings of a few birds in those elms where they sometimes gathered in singing droves brought back, like a gasp, the emotions of the past. How frightfully desirable all that seemed! I could, I suppose, have driven to the village and probably found Freddie there, but it was not Freddie whom I wished to see—it was chiefly Milly, and after her, Dan. The wind blew at me. Trees were beginning to rock, waves to roll, long grass to lean. The thunder was much closer, sounding, in those hills, like a lot of boards being dropped one on top of the other in quick succession. I was consumed with regret: I wanted the past again with a wild hunger, I wanted to live it over more blithely. And I said, How foolish!

That was late in 1929. I knew as well as anyone that you cannot have the past again, in any year, but I did not know that I was never again to come back to Silverton. And yet, of course, you always do have the past, and I did not know this either—you always do have the past in the sense that it has already settled your future in some degree, and probably, to that degree, spoiled it.

TWO

Winters in the City, Older

1

A windy, wintry tunnel of a crosstown street in the West Forties. A small hand in a tautly drawn white kid glove on my sleeve. I turned. A veiled face that was laughing. Snow blew desultorily between this face and mine. “Grant Norman?”

It was Milly Moore.

“I saw you from my cab, and I knew at once—I couldn’t have been wrong! Darling, get in there with me out of this wind.”

The driver had double-parked and the door of his cab stood open. “Milly. Good God.”

“Darling, get in!”

“I can’t. I’m late for an appointment. Right here. But look—”

“Grant?”

“When can I see you?”

Horns were blasting impatiently. The cab driver tapped out a quick summons to Milly.

“Do you live in New York?”

“Yes.”

“Are you in the book?”

“Yes.”

“Darling, I’ll call you.”

One more long glance through the spotted veil, with the filthy city wind blowing gray snow down at us, and, “Darling Grant! This is wonderful!” Then she ran.

“Milly! Wait!” I called, but she had gone. I watched her slim ankles above the steep black calfskin heels, and then I watched the cab pull away an

d saw the gloved hand lifted at the smirched window. It was over.

Had it happened at all, I wondered as I bought the newspaper that I had stopped for, and was pushed and shoved by less visionary comrades. I knew quite well what day it was, and what year, and yet my eye settled, as if for confirmation, not on the headline of the paper that I held, but on January 10, 1938. Snowflakes fell on the paper and left marks like those of tears.

Milly did not telephone me. She wrote, instead, a note that came next day to my Tenth Street walk-up. If she had telephoned, she might have prepared me for those developments of which I was still ignorant, but her note told me nothing that was new and too much of what was old. If you honestly want to see us, Grant, come for dinner on Friday, it said. It’s against the law to hunt birds’ eggs in the Park, and it’s winter besides, but there are other ways in which we can recall for an evening at least that time which only you, apparently, have been willing to forget. Come at seven-thirty. The note was signed simply Milly, and there was an engraved address at the top of the sheet—a Fifth Avenue number in the Eighties. The business of the birds’ eggs I found rather chilling, and it was that about which I wondered rather than about identities—to whom the plural might refer, for example; I simply assumed, foolishly, that Gregory Moore and his wife were now in New York and that Milly lived with them. My keeping her thus enclosed in the situation of her youth may have shown as much about my relationship to the past as her note showed about hers.

Friday was the next day. The address was for one of those monstrously solid granite apartment buildings with a gilded grilled entrance meant to suggest a palace of marble. I asked the doorman for the Moores’ apartment, and was told that there were no Moores. I pulled out Milly’s note to ascertain the address and I showed it to him.

“There is Mrs. Ford, whose name was Moore. Do you want Mrs. Daniel Ford?”

He had everything all mixed up, I thought impatiently, before the jolt of the fact struck me, and then, “Of course,” I said, and managed through my shock weakly to add, “I forgot.”

He gave an order, and the elevator boy stiffened for me and pulled back the door.

Should I have known? Why? I had nearly forgotten them in my own concerns. As we had moved apart, so had our worlds, and now, as the elevator lifted me up to them with velvet swiftness, that gap of worlds seemed to stretch almost frighteningly wider. Who were they now? And who, for that matter, was I? I had no desire to account for myself to them, to tell them how, after my mother’s death, I had, for example, spent my nights in fifty-cent hotels, or how, after my father’s death, which came first, I followed my mother west and became the hovering, incompetent, and unwilling protector of her poverty.

At Christmas, in 1929, my father’s gift to my mother was a bottle of bootlegged Scotch which she discovered only after the janitor in his office building had called the police who in turn had called on her to say that my father had gone down there that morning to blow out his brains. Everything was lost, and the house on Waverly Place, like the house in Silverton, and the contents of both, were not even ours to sell. I had been enrolled in a New England university and I managed to finish out the term, but by the end of it, my mother, as if searching for her home, had already gone to California with little more than a trunk of clothes and an inadequate annuity. In February, I followed in a day coach.

She had no relatives to speak of there, only a distant cousin or two by that time, and no real friends any longer, but San Francisco seemed to promise her some refuge after the savage reversals of New York. Yet when I arrived, I found her already disappointed, lonely and querulous in a small apartment on Russian Hill where she sat staring out of her large window at the usual items—the bay, the Embarcadero, a piece of bridge, Alcatraz. There was no room for me and she had of course hardly enough money for herself.

I enrolled at the University and lived in Berkeley, hashing in a sorority house and sleeping and studying in a basement room in a tennis club where, in exchange for the room, I acted as night watchman and where, too, when I was lucky, I picked up a child or two on the courts as a pupil. They were difficult, threadbare years, and I was glad when they were over, even though the best that I could manage then was a job as copy boy on a San Francisco newspaper. Everyone on the paper was expected to learn to write in a cozy tone of heavily domestic irony that I never quite managed in the small assignments that began to come to me, and the political views of the owners and the editor, maintained with a Parnassian detachment from the realities of 1933 and 1934, constantly irritated me. After eighteen months, I was let go, and at almost exactly that moment, my mother let go. Night after night, sitting in her small and by now rather shabby prison, a ruined old woman not yet fifty, she stared out at the lights of that other, larger prison, until one night when fog blurred the city and no lights seemed to belong to objects or even to represent them, she emptied a bottle of whisky and took enough nembutal to put an end to her pointless vigil. I found her the next afternoon in her chair, with her hands open, the palms cupped a little, as though she were begging for something.

Now came the fierce time for me, when I did beg, until, after six months of nothing, I found a job on a union paper that I suited and that suited me. My life slipped another notch as it was drawn closely into the tough intrigues of the water front, but out of this experience I was able to write occasional reports on west coast labor that found their way into liberal periodicals in New York, and these reports brought me, finally, an offer from one of these periodicals, The New World, to come to New York as a staff writer. I had been there a little less than a year, and now, as I stepped from that elevator into the foyer at which it stopped, I felt as much a stranger to myself as whatever life lay beyond it had become a stranger—alien, as when a child, staring into a mirror, suddenly sees himself there as someone else, an imperturbable interloper, a stranger in his place. It had been a long time since I had felt such a deep, detached sense of my life’s not being in the least my own. I looked at my gloved hand as it hovered over the button that would ring a bell inside and admit me, and my hand was like some totally unfamiliar object. Then of itself it plunged, and almost at once the door flew open and I was engulfed in arms.

Milly’s arms, around my neck, were bare and perfumed, and I was looking down into her blue eyes, dazzled with tears. The heavy, man’s arm that was around my shoulder and the hand that was thumping me were Freddie Grabhorn’s, and to look at him, I had to lift my eyes. He was half a head taller than I, as Milly was half a head shorter. They were both talking and laughing, and I was laughing, and for a moment everything was confusion as we stood there enclosed in that senselessly babbling embrace. Then all arms abruptly dropped and we stood separate, smiling, before closed doors, and I knew that I had, through this welcome, been returned to myself.

Milly’s smile faded as she put her hand on a great, ornamental knob. “Before we go in, Grant—I have to tell you this. Be careful of what you say when Dan is with us.”

“Of what I say?” I was still smiling.

“It’s important, Grant, that you—” Freddie began with an expression of utmost solemnity, but Milly broke into his speech.

“Let’s not stand out here any longer. Come in. We’ll explain.” She opened the door and we entered the generous vestibule of the apartment. There, among tapestries and large mirrors with heavy, rococo frames, Freddie took my hat and coat.

“What’s wrong with Dan?” I asked then.

Milly’s voice was hushed now. “He’s so easily upset. Ever since his parents—ever since that terrible accident—it’s been very difficult.…”

“You know, Milly, I’m absolutely ignorant. I’ve been three thousand miles away from all of you, and for almost ten years. I didn’t know you were married. You’ll have to start at the beginning.” I had answered in a whisper, too.

Then Freddie whispered, “Unpleasant things upset him. He’s likely to go to pieces when he’s reminded.… Any kind of violence.… You’ve got to remember t

hat anything unpleasant at all may remind him.”

Milly was looking at me intently, Freddie was looking at me severely, and I did not yet understand at all why both of them spoke with that portentous quality in their secretive voices, or why, indeed, I should suddenly have found myself the center of that hushed conspiracy in the vestibule. But their lives, I was to learn soon enough, were lived in an atmosphere of intrigue, and not only the intrigue that attaches to Dan’s business, oh no, not only that. Had it been only that, there would be no story for me to tell.

“The beginning …” Milly was murmuring vaguely. “You didn’t know we were married, Grant? Yes, we must start at the beginning, if we can.” She seemed unable to be more definite, and looked at me with a helpless lifting of the eyes and a kind of plea in the sudden sharp elevation of her hands. Then, smiling brilliantly, “Oh, but it’s good to see you!” she cried in her friendly voice, and seized my arm. “Darling, come in!”

And then, after all that, Dan was not there.

It came to me that I had never seen Milly outside a country setting, that she had always been that free and striving creature of the summer, and that as I had known her, there was almost nothing that would have promised this. She stood before me in a long black gown of perfect severity except that the deep neckline transformed itself into a tall rolled satin collar that suggested the corolla of a calla lily if one could imagine a black calla, and from this rose her throat and lovely head, with the fair hair pulled severely up and back and fastened in the simplest twist, a housewife’s bun, where she wore a blue flower. Her beauty had grown, somehow, to exist in its calm, when she was calm, a development that one would no more have predicted than one would have predicted that she should have chosen such an establishment as we were now in as proper to her.

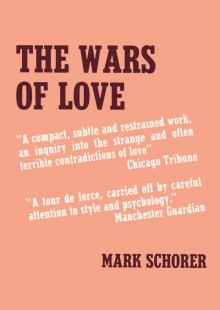

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love