- Home

- Schorer, Mark;

The Wars of Love Page 10

The Wars of Love Read online

Page 10

My heart shrank: literary allusion or not, she was forcing herself to say good-by; I had lost. And I felt an impulsive rush of cruelty. “Surely nothing that I said can be worth your tears.”

Her face was soft and wounded. She brushed at her eyes with her handkerchief, and she said, “Yes, enough of what you said is true or true enough to make me—” She broke off impatiently and blew her lovely nose.

“Make you what?”

“I’ve never seen your apartment, Grant. Take me there, won’t you?”

In my abrupt humiliation, I gasped and used her word, “Darling!”

I took her arm and we turned into Fifth Avenue and walked silently for a while in the melting, late March afternoon, on slushy sidewalks. She walked with her head down and passively allowed me to steer her through the crowds. There was a rather terrible sense of joyless fatality about that walk, about her, even about the delicate arch of her bent neck over the brown furs, under the frivolous hat. We got on a bus presently and as we rode downtown in silence, it occurred to me, as, day after day, it had to every man of good will, that we were in the infamous month of Anschluss, when an unwilling Austria submitted to a tyranny that she was half-convinced was necessary to survival. Now the thought of a decreed debasement impelled me to turn sharply to Milly, to try to find some warm thing to say to her. She looked at me and smiled gently, almost shyly, and her smile made it unnecessary to say anything. I let my shoulder rest against hers and pressed her arm, which I still held.

At Tenth Street, we got off the bus and walked the few blocks east to my building, and then I led her up the three flights of stairs to the shabby two-room affair that was my apartment. As soon as we entered, she stopped before the false fireplace, and stared up at the poster from Barcelona that I had tacked up over the Travertine marble mantel. It was a large sheet, perhaps five feet by five, and it showed in the lower foreground a phalanx of bare, lifted arms, and above them, printed on a blue sky in letters of blood, the single word Salud.

“Salud,” I rather foolishly said to Milly, who turned and came surprisingly into my arms. Our lips just touched, and there was a mingling of breath, and I said to myself, easy, easy, as our lips trembled over that promise of a kiss. Then Milly lifted her hands to remove her hat, and I released her. She dropped the hat on a chair, unfastened the furs at her neck and let them fall beside it, and then unbuttoned her jacket and tossed that on the chair, too. She was wearing a filmy white blouse that gave her a rather prim air. Then she sat down on a worn studio couch and peered at an anti-fascist calendar drawing by Gropper that hung on the wall beside her.

“So this is where you live. It is different. You’re right, I see—”

I sat beside her and pulled her softly back into my arms. “Dearest girl, we have a language,” I said, and then began that first kiss, which must do everything for me and undo so much of tightness and of fear in her. Gently, gently it began, that first soft trembling of the lips together again, and then more firmly pressing, then parting, the hot breath together, the tongue slowly pressing, exploring, finding, mouths opening together, pushing, searching, sucking, deep, deep, bodies straining together, straining, arching, and then, “Oh,” she moaned suddenly and long, and collapsed against me, her head down on my chest. I murmured in her hair and stroked her, her back, her shoulders, her neck, her cheek, then lowered her body in my arms, and then began again, first softly, softly, lips quivering, resistance flowing away again, lips opening, tongue, breath, pressing, begging, demanding, deep, deep, and longer now, longer, bodies straining again, forcing, arms tight around, tight, tight, and then again “Oh-h,” the sudden moan, the quick collapse, and something torn away, something broken.

“Darling, darling,” murmured only, and then my arms under her, lifting her. I carried her into the bedroom, where the light was gray, and laid her on my bed, helped her with her clothes, then pulled off my own. When I came to her, I put my face on her stomach, touched her small, girllike breasts, brushed tenderly the maidenly flaxen hair, then stretched beside her, flesh against flesh now, soft and hard, hot, and the kiss again, slow, slow, more softly, more softly, the draining away of will and separateness, then harder, deeper, harder, deeper, longer, longer, wash, wash, wash, and now no separateness, entirely together, no will, no nothing but slow wash and wash of hot blood and then slow rock, rock of ocean in us, wash and rock, wash and rock, wash and rock, and oh! she was mine, she was mine.

And so, in a sense, April of that year became our month.

3

April, May, and half of June. It was lovely, and it was strange, too, because it was, alas, incomplete, as perhaps I should have known that it would be, since it is almost certainly true that any idyl must also be a fragment. Yet one may ask whether any life, in all its parts, can be one and whole, and find, perhaps, in the very nature of things, some justification for the partialities of our experience.

That it was an idyl, even under the somewhat grimy circumstances of my life, is true. At the end of March I gave up my downtown apartment and took a single room at monthly rates in a midtown hotel, just a step across the street from my office, and here Milly came, when we both could manage, during my lunch hour. Sometimes she brought my lunch for me; sometimes we had sandwiches sent up for us. That was our place and our time, above the crash and bang of Forty-sixth Street traffic, in an impersonal box of a room where soot was always on the sills, with metal furniture finished in a brown, halfhearted simulation of wood, with a hard, worn carpet on the floor and two pink and blue and pale green prints of romantic subjects in gilt frames on the dun walls. The only merit of this place was its convenience and the fact that, just because it was so rather horribly neutral, we could, when we were together, be impervious to it.

That was our poor fragment of an idyl, closed off from nearly everything, and confined almost entirely to that room, that hour. Twice Milly appeared, after a hurried pay-phone call, rather late at night, on some ruse, in a pitiable attempt to show that, on our account, she was willing to take that risk. But more she would not risk. I tried to persuade her to come away for just one week end, to say that she had to go up to Albany and then go, instead, to Fire Island or some country hotel, so that we could have at least two days together, uninterrupted, in the spring. But she would not. She would not, as she would not let our relationship touch the rest of her life. And so, in the end, it became almost intolerable—in minor ways for me, in a major way for her.

She changed for me. She changed, as I had hoped for her sake that she could: but the terrible thing was that she changed for me alone and not in her whole person, so that for her this was merely a further act of self-division. We would meet in that implausible room and she was entirely mine and entirely what I would have had her be: frank in her passion and wanton with it, and afterward, in the murmuring relaxed tenderness that proved the consummation, gentle and humorous, alert and interested if we talked (and these occasions were our only time for talk), sometimes sleepy. Sometimes she said, “I want to sleep here for a while,” and I would leave her in that bed. When I came back at the end of the afternoon, the room was entirely in order again, as though no one had been there at all, but mingling with the dry, city air of the room, a faint ghost of her perfume. Or we would lie in that rumpled bed and talk—I would talk, I suppose—talk in those months of Spain and Germany and Roosevelt. I tried to interest her in the world of ideas and events within which my work existed, and she would listen with a sweet patience, but she had, in fact, no real interest in ideas or events, and listened only on my account, her body close, her mind either empty or away, and words would drag and stall at last, and we would dress again, and part in the street presently, with a last quick gesture of embrace. And then if in the evening I went to the apartment on Fifth Avenue, as I often did, it was almost as if we had not had that gulp of passion at all, only a few hours before, almost as if we had nothing between us that was our own. A quick pressure of the hand, a word of endearment delivered sotto voce to set i

t off from all the loose endearments she was given to, a wry smile, a long glance: these were the conventionally secret and unsatisfactory tokens of our conspiracy, the intolerable reminders that our love had no relation to anything outside and that, because it had none, was hardly even a deceit. And while it is true enough that I had had no very clear expectations of what should come of it, I had certainly miscalculated the human chemistry, which I had thought to have certain inevitable characteristics. On the contrary. Those categories of an outmoded psychology—head, heart, and loins—seemed not at all outmoded here, for Milly’s head, if one means the calculating portion, was Freddie’s still (there was some alliance there that I could not fathom, and an alliance unaltered by my intrusion or the fact of our alliance); and her heart, if one means the merely sympathetic nature, was Dan’s, as before; and the third was mine. And this surely was an intolerable situation for her.

My hope had been that she would heal her divisions and find an identity through me. Hers seemed to be to find it in us, in all of us—to divide and extend herself, and by binding us together in the constantly revived and reconsidered ambiente of the shared experience of our youth, somehow bind her life together, and her being. It is impossible to say to what extent being is autonomous, and to what extent it exists in relationship, or even in what intricate way these two are balanced in the human economy, but here there was no balance at all, there was only a kind of war. And as I lived with her and with them in this queer warfare, it seemed to me, as it had on my first evening with them, that it was Freddie who, somehow, was at the root of it, Freddie who held the secret and Freddie who did the first damage, Freddie who most needed them, and Freddie, therefore, who most injured her. That was the line I must pursue if our love was to be of any use at all, or even if it was to survive.

In those three months, on the occasions when the four of us were together, it was always Freddie that I had been watching, but I learned nothing. We were frequently together, chiefly at concerts but occasionally at the theater, and one week end we spent in the country, and then we walked and swam together as in the old days. Freddie and Dan and I were all off our swimming form and short of wind, but Milly was as good as ever, and when she dived, she was a marvel. Watching her in perfect control of that body that was so meaninglessly mine, I felt a stab of jealousy that almost tempted me to take Freddie aside and blurt out the truth to him, tell him and shatter him, once and for all. But then, watching him in his gawking approval of Milly’s grace as, over and over, she went off that high board like a bird, I relaxed again: he seemed too stupidly happy to disturb, too innocently admiring, suddenly, to merit suspicion of anything. I would have to find another time, some other means.

An interruption loomed ahead. As May of that year came toward an end, and war in Europe became a clear inevitability, this country seemed to enter upon a period of industrial prosperity, and the newspapers wrote of what they called the “Recovery.” My editor, who viewed the boom with a properly ironic suspicion, asked me to undertake a swing through the major industrial areas in the country and to write a series of on-the-spot reports for the magazine. The project would take most of the summer. Dan and Milly, meanwhile, had taken a place for the summer on the Connecticut shore, where they had previously been, and while this had not been said, Freddie, I suspected, would spend most of his summer with them, or at least as much of it as was left free to him by the business of the gallery, which they closed during July and August.

“If you could come with me—that would make it mean something!”

We were on my bed, I half sitting up, she lying, her shoulders on my arm where I leaned upon my elbow. That evening I was to leave for Detroit.

“Ah, Grant—don’t plague us with impossibles.”

“I know.”

She looked up into my face. “You’re not satisfied?”

I could not answer. Instead, I asked what I already knew. “You never go to Silverton in the summers any more?”

“The Ford house is up for sale. We’ve told you, haven’t we?”

“Why is that?”

“It would be impossible for Dan. All his deepest memories are there, the reminders would be constant.”

“But he has his father’s business, you live in his father’s apartment—”

“I think that we should move. To some wholly new place. Dan’s not getting better. Have you noticed? He broods more and more.”

I hesitated to say what I had long wanted to say. “Don’t you think you miscalculate Dan’s needs?”

“How?”

“Protecting him as you do, you imprison him in a way. Imprison him with nothing, or with nothing but the very thing you want him to overcome. But he has no means of overcoming it.”

She looked at me gravely. “I hope you’re not right,” she said.

“Doesn’t Dan ever want to go back there, to Silverton?”

“He never speaks of it.”

“Freddie—well, of course, he positively doesn’t want to, does he?”

“No, I don’t think he does.”

“Did you ever meet his parents?”

“Freddie’s?”

“Yes.”

“No, I never did. They really mean nothing to him.”

“That’s curious though, don’t you think, Milly?”

“Is it?”

“No connection at all, I mean. Just a blank. After the youthful revolt, most people make an adjustment—they want some connection—”

“Hasn’t it occurred to you that more is curious in our situation than only Freddie? Hasn’t it occurred to you that here we are, four of us, and none of us really has parents? You and Dan have none in fact. And in effect, Freddie and I have none. That’s perhaps what links us.”

Her remarks made me impatient, and “Orphans in the storm!” I sneered mildly.

“Well, yes, if you wish.”

“Sweetheart, don’t be silly. You’re nothing like Freddie. Your mother is also really dead. And your father—he never had any room left for you, did he? But Freddie—he’s just a snob, don’t you see?”

“No, no.”

“What is Freddie anyway? What’s he like inside? Sometimes I have no sense of him at all, as a person.”

“What a strange remark from you, Grant, having known him ever since you were a boy.”

“I know. But sometimes I don’t really know him at all. I mean—I feel there is a kind of emptiness in him that is not to be known, because there’s nothing.”

“Oh, you’re being unfair!”

“And at other times I feel strongly that what is there is some secret, something concealed and sinister—”

“Nonsense.”

“And I can’t relate him now, very much, to the boy he was. In those slick, shoulder-padded gabardines he wears, with his sucking attachment to you and Dan—it’s just hard to believe—that kid in overalls who could kill a crow with a slingshot!”

“Well.…”

“Freddie’s really a fascist, I think.”

“Oh, nonsense!”

“Not only politically. Although there, too, I’ll venture. But in a larger sense than in his rationalized attitudes alone, as towards Spain, for example. Temperamentally, I mean. The emotional ruthlessness. The absence of inner support that impels him to his external aggressiveness—in his personal relationships, I mean. Notably, of course, with you and Dan.”

“Now you’re being silly!” she laughed.

“Silly? I wonder. Dan and Freddie together—Dan’s like a small, highly cultivated, peace-loving country that’s just been moved in on.”

“Ridiculous. Freddie is just marvelous for Dan, he’s been a lifesaver in the gallery, for example. And as for other ways—”

“How necessary is he to the gallery, really?”

“Well, you know, Grant—or don’t you?”

“I know he does a lot there. I know he thinks he’s necessary. And that Dan does, too. But in a real sense, is he?”

“Of course. It�

��s really Freddie who’s responsible for the present character of the gallery, for all the changes. Dan’s father was mainly interested in eighteenth-century French and British pictures. Now it’s contemporary and modern, bright, even Americans—”

“But wouldn’t it be better for Dan if Dan were allowed to have the full responsibility now? Perhaps that was impossible at first. But now. Wouldn’t it be?”

“I can’t imagine it.”

“I can,” I said. “It’s what Dan needs.”

She closed her eyes and stirred restlessly on my arm, then lifted her hand and put it on my chest. “Stop talking, dear. Our time is passing.”

“Ah, Milly—” I slid down beside her. “How stubborn you are, under this soft outside!” Her arm went round my neck, her mouth brushed slowly over mine, back and forth, our arms tightened, and we were in the embrace. How different now, how quickly, with the habit of our life, the separateness flowed away and she was there for me! Then slowly, slowly.…

“I’ll miss you so,” she murmured. “I’ll miss you so.”

“I’ll miss you,” I murmured in reply. “I’ll miss you.”

“Oh, Grant, dear Grant—”

“You do love me?”

Slowly, slowly, our mouths lying lightly together, breath mingling. “Grant, Grant,” she said, her arms tightening.

“You love me most?”

Her mouth on mine, clamped, but no words in reply, as faster now, faster, and I lifted my head.

“You love me most?”

“Grant, dearest, dearest.”

“You love me most. Say it. Say it. Oh, say it!”

Her eyes were shut. “Dearest, dearest.…”

“And get rid of Freddie.”

Her body jerked, her arms tightened, “I’m not listening!” she cried, and the shuddering spasm was upon us. Then, in the morbid quiet, when she opened her eyes on me again, she only repeated, “I’ll miss you so,” as if no outrage had been committed, and I did not then press my point.

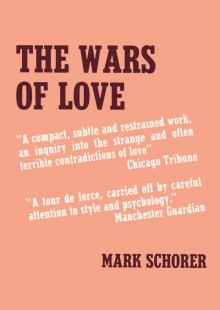

The Wars of Love

The Wars of Love